1970-1972

In Spring 1970, Danny Yung phoned his sister, Eleanor Yung. He gave her an address in Manhattan’s Chinatown and told her to meet him there. After an hour long subway ride from the Upper West Side, Eleanor stood on a stairwell leading to a tiny basement, trying hard to match the expression on her brother’s face. Danny stood in the middle of the basement at 54 Elizabeth Street. He excitedly asked, “what do you think?”

Eleanor thought the obvious.

“It’s a basement.”

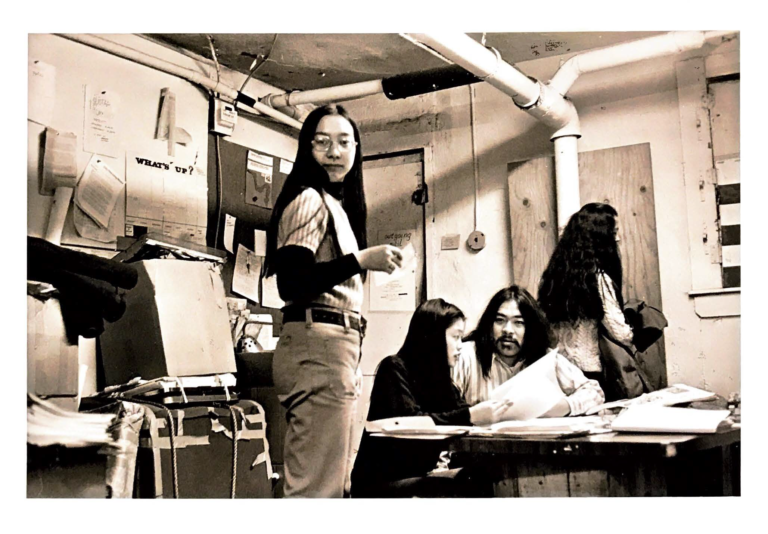

This dark, tiny basement in the middle of Chinatown would soon become a centerpoint for Asian American activism in the city. Housing the organization within the confines of the neighborhood was a critical part of how members came to consider the Chinatown community as part of their larger, extended Asian American family.

Members of the Basement Workshop worked alongside other community organizations to ensure Chinatown residents were equipped with crucial social services. The 1970 US Census was the first in history to be conducted through mail-in forms. As many Chinatown residents were not bilingual, or were housed in multi-family homes, volunteers including Basement members knocked on doors and helped residents fill out forms and translate information.

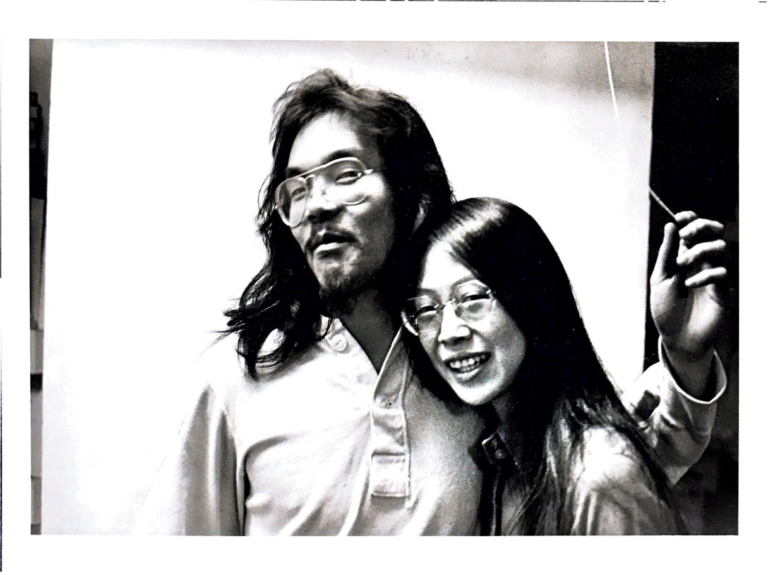

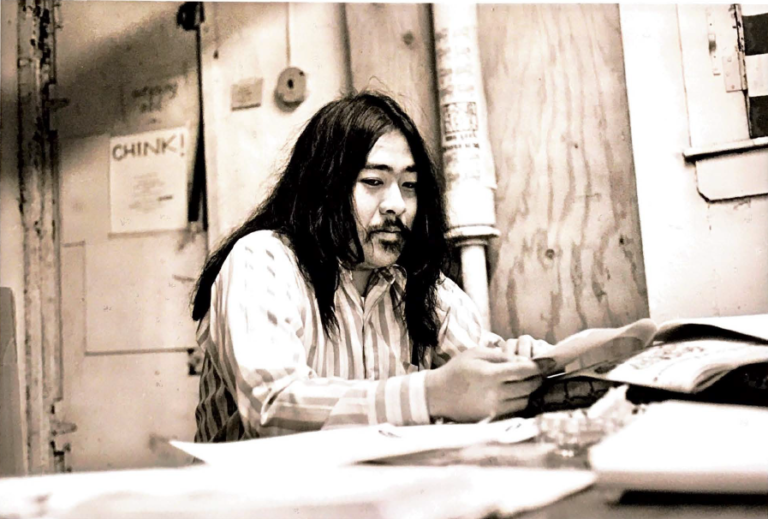

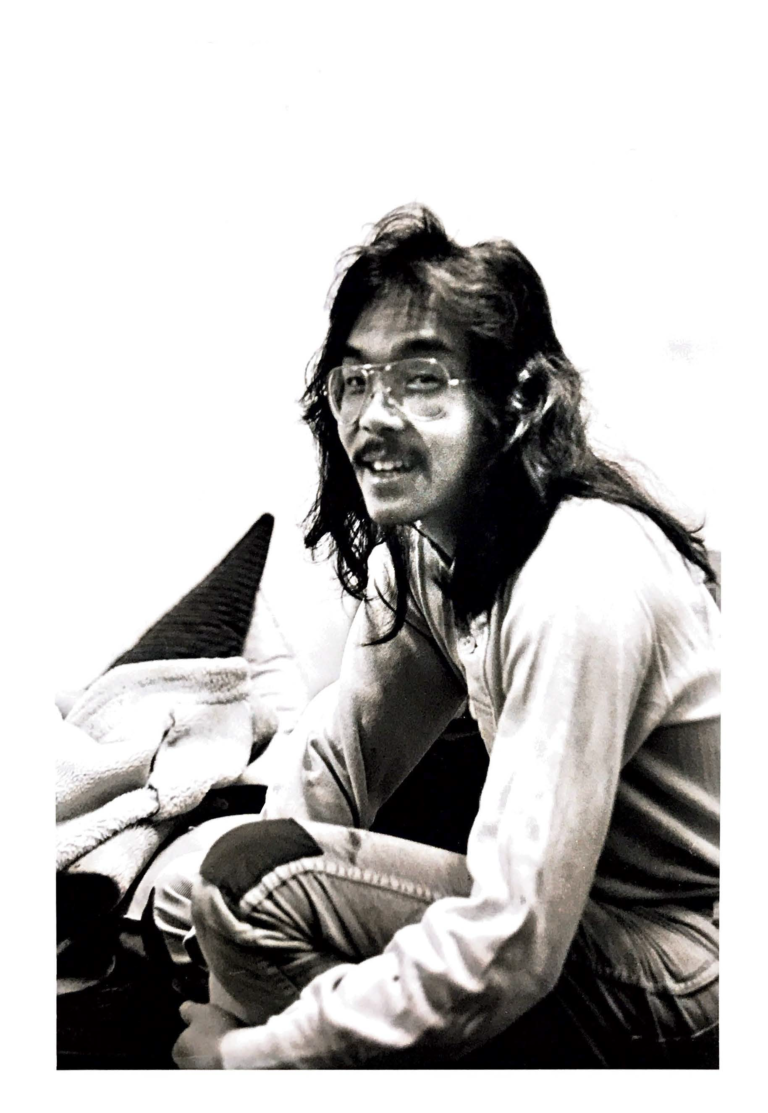

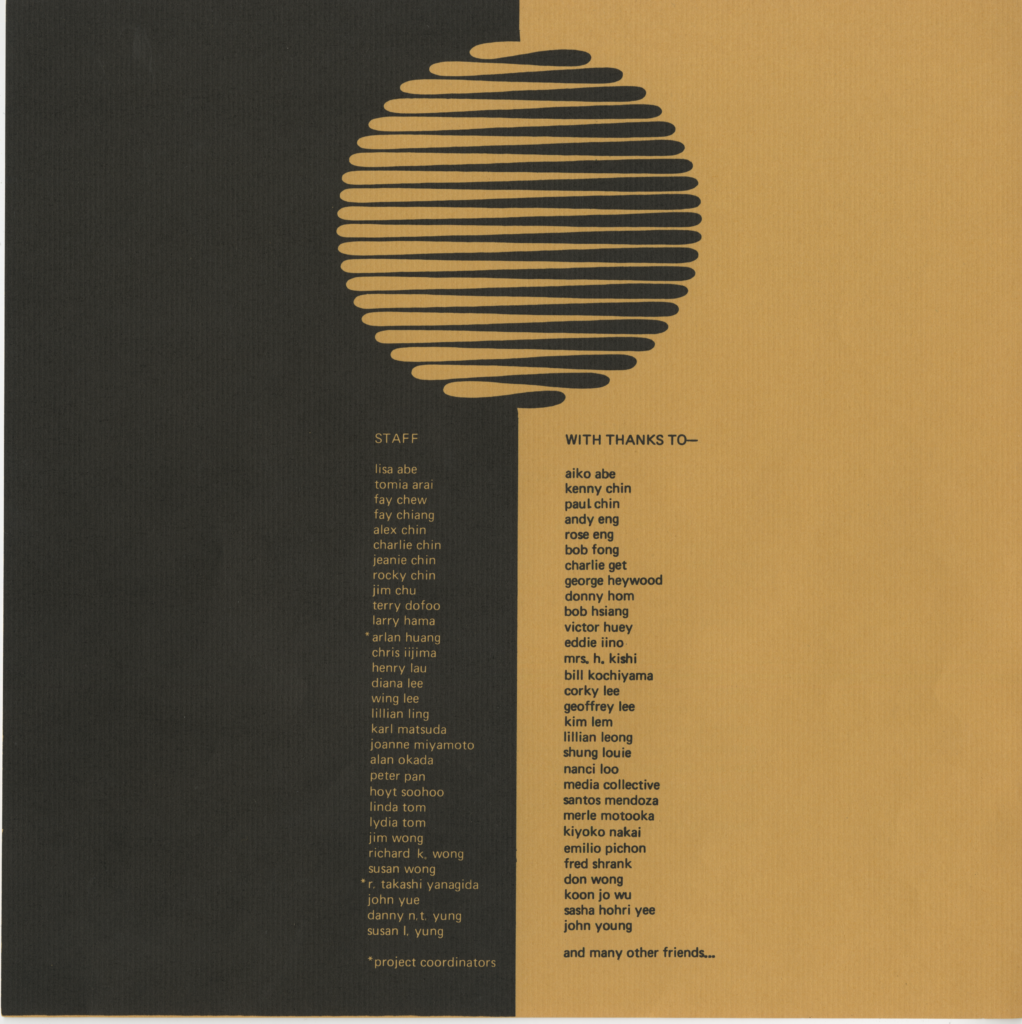

During this time, Arlan Huang and Takashi Yanagida worked as co-coordinators for a new arts anthology called Yellow Pearl. Inspired by the music and lyrics from A Grain of Sand (an Asian American folk band formed by Charlie Chin, Chris Iijima, and Nobuko Miyamoto), a group of over 31 members of the Basement Workshop sent out an open call for writing and illustrations to accompany the band’s lyrics.

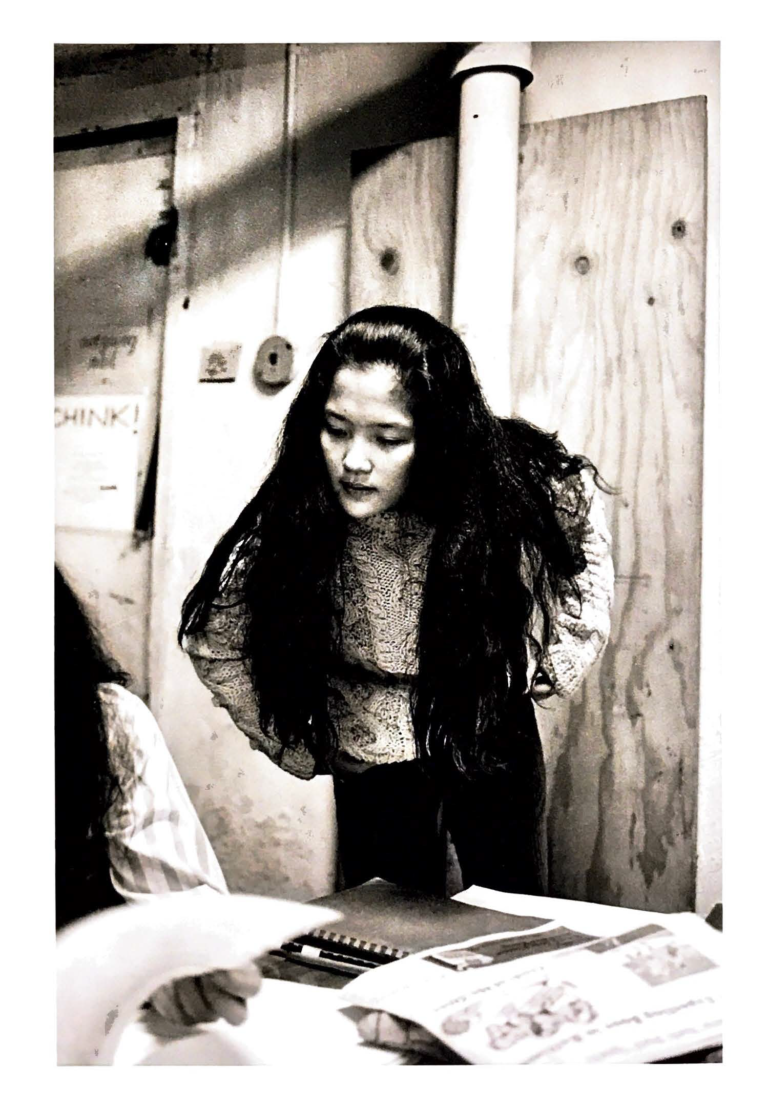

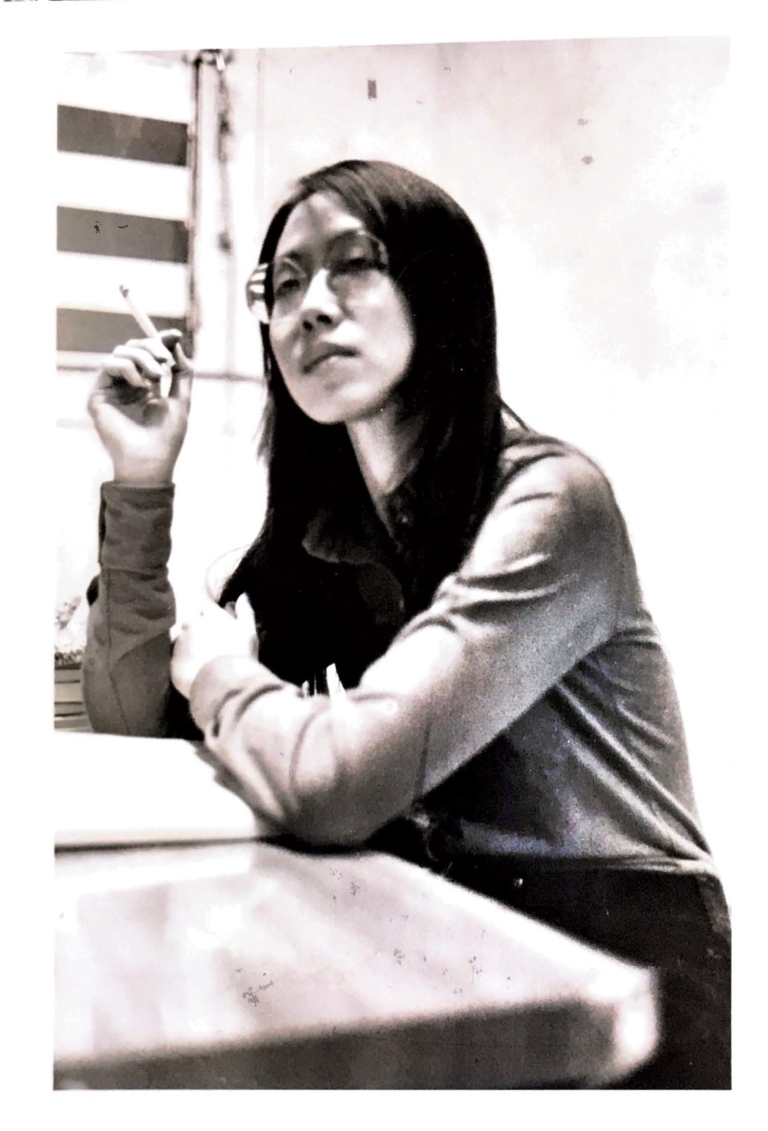

With a variety of interests and social causes represented, young Asian Americans flocked to the basement to help in artistic pursuits, put on community events, and brainstorm further ways to advance Asian American social activism.

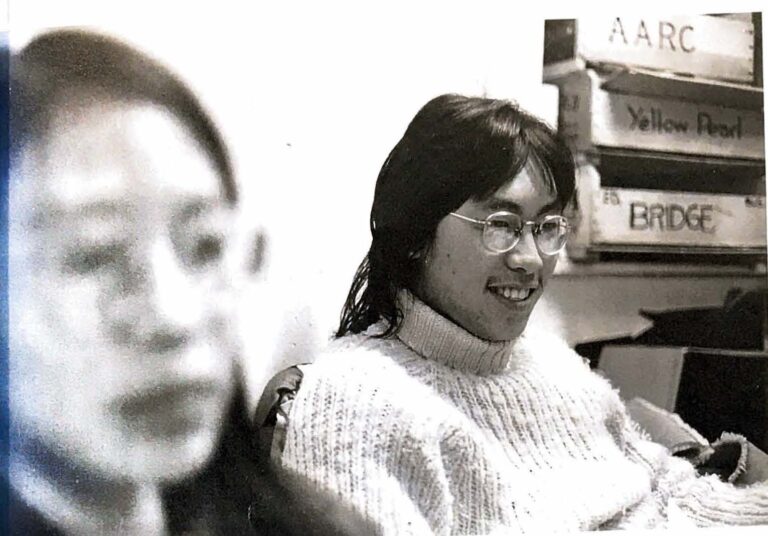

Alongside the team working on Yellow Pearl, the basement at 54 Elizabeth Street was home to the Asian American Resource Center. What began as a couple of dingy filing cabinets expanded into a repository of Asian American writing, research, and miscellaneous educational materials. Headed by Rocky Chin, the AARC grew quickly.

Folks at the basement soon realized that the tiny space on Elizabeth Street could no longer hold them or the ideas they had to improve their communities.